Pirahã Language: Does It Represent an Era in the Linguistic Evolution of Humanity?

- azmiaydin

- 23 Ağu 2025

- 5 dakikada okunur

How we learn and speak a language remains a controversial topic.

For many years, Noam Chomsky’s views dominated this field. In response to the question of how we acquire language, he argued that we possess a universal language faculty — a capacity that is shared by all humans and can almost be thought of as an organ of the body. This is a capacity unique to *Homo sapiens*. He viewed this language faculty as a “bodily organ,” alongside other cognitive systems.

Thus, based on this innate linguistic faculty, a child begins to speak naturally and rapidly within their own social context. Chomsky calls this the "Language Acquisition Device (LAD)" — a structure that babies are born with in their brains, which matures over time and allows them to learn and understand language quickly.

This linguistic faculty, being genetic, is said to contain a "universal grammar." In other words, although there are many languages in the world, they all share a common grammatical structure.

Chomsky describes his theory with an analogy: “If a Martian were to land on Earth, it would say that all spoken languages derive from the same basic structure and differ only on the surface.” This is a metaphor, but also a guide, because if we know how a Martian would think, that Martian is essentially us. If a “Martian” had a fundamentally different mental structure, it would not see things as we do.

So, what is the key feature of this language faculty?

According to Chomsky, at the core of our language faculty is a feature called "recursion" — the ability to embed structures within structures. For example: “Ali told me that Can told Mehmet that Hasan said he is a good man.” Recursion, Chomsky argues, is the fundamental property that separates human language from other forms of animal communication. This raises an important question: in proposing this theory, what theory is Chomsky actually rejecting?

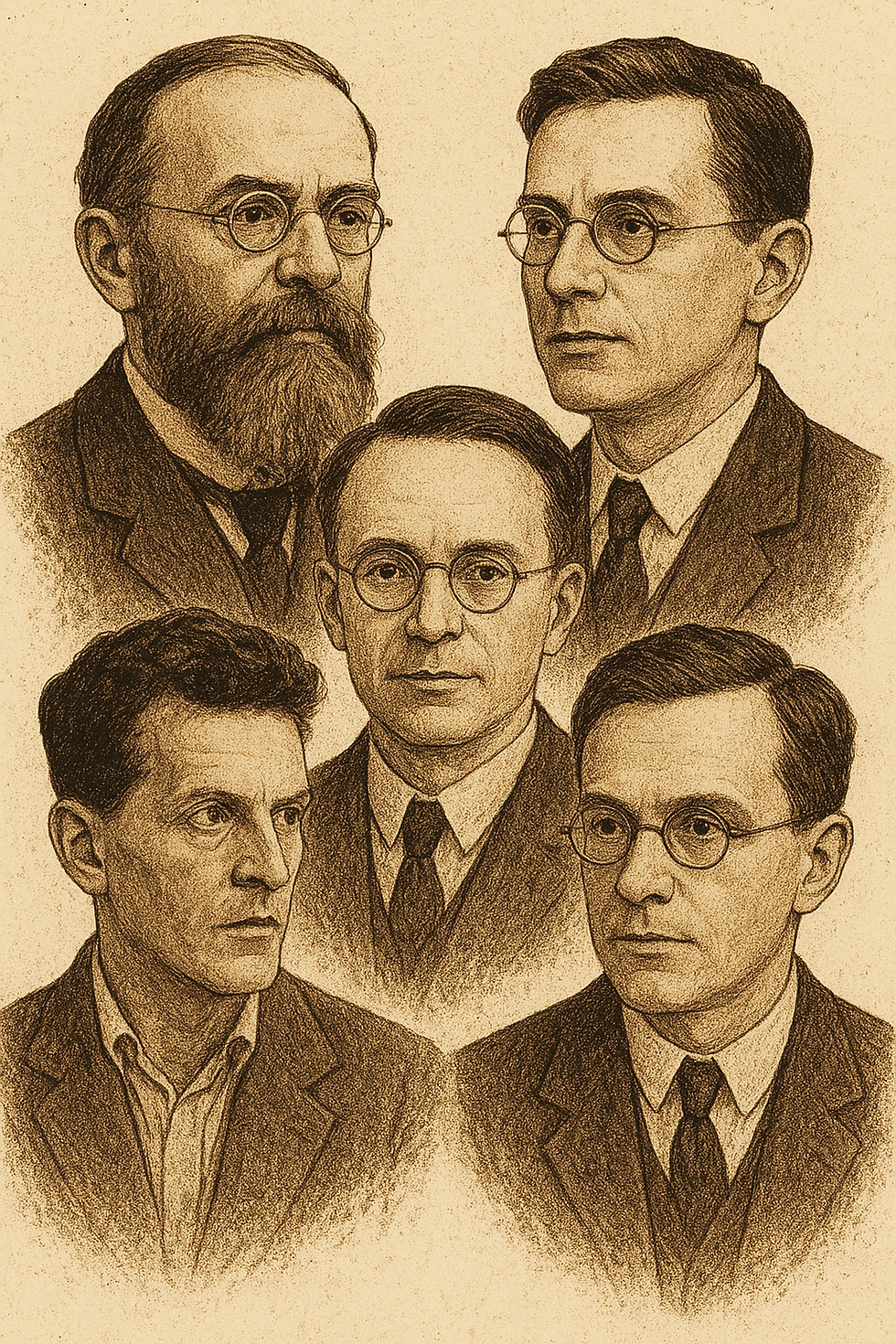

What Chomsky rejects is the idea that language developed through "evolution". His theory, which dominated academic circles for decades, was later challenged by the work of linguist Daniel Everett, who studied the Pirahã tribe and their language in the Amazon rainforest. Everett, who initially went there to teach Christianity, ended up living with the tribe for many years.

The hunter-gatherer Pirahã culture and language have striking features. Their language lacks complex recursive compound sentences, lacks verb tenses, and lacks numbers. They can communicate through whistling. They use only "11 phonemes". Instead of numbers, they say “a few” or “many.” They don’t deal with past or future but only with the “here and now.” Everett argues that "recursion" which Chomsky considers the core feature of human language, "does not exist in Pirahã."

Everett developed a theory opposing Chomsky’s. According to him, there is "no universal grammar"; our language capacity is "not innate", recursion is "not necessary", and language evolves according to "cultural needs". To answer the question posed at the beginning of this essay, Everett says: “Language was invented and developed over time. Languages constantly change — sometimes becoming more complex, sometimes simpler.”

To support his thesis, Everett turns to human history and argues that the **invention of language dates back to Homo erectus**.

*Illustration of Homo erectus — adult female head by Tim Evanson. Full-body male figure, Britannica.*

Everett claims that “Neanderthals and Sapiens were born into a linguistic world.” Homo erectus, with a vocal tract similar to that of a gorilla, was the first human to walk upright and the first to use fire. Fossils show they lived about 1.9 million years ago, with remains dating back 200,000 years. They were similar to us in height and weight. Excavations at a recently discovered Homo erectus settlement (the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site, dating back around 750,000 years) show evidence of living spaces with designated areas for processing plant and animal materials. Their crafted tools, shaped stones, and distinct spear designs indicate organization, hierarchy, and communication. This need for communication, Everett argues, is what led to the invention of language.

Everett’s papers and books not only sparked academic debate but also triggered **personal attacks and hostility**. Chomsky called Everett a “charlatan.” In their debates, they accused each other of being “shameful.” Everett stated that Chomsky’s influential academic circle often subjected him to harsh, even insulting, criticism. Critics argued that no one but Everett truly understands the Pirahã language, and that there is insufficient research to conclude whether recursion exists in it. Chomsky countered that even if such a language existed, it would not disprove his theory. He also claimed that Pirahã speakers already speak Portuguese, making the debate pointless. Everett responded that only one person in the tribe speaks Portuguese, and that person, having lived outside the tribe, does not know Pirahã well enough.

But could there be a different perspective between these two extremes?

My suggestion is to rethink this debate through the distinction between ontogenesis (the development of the individual) and phylogenesis (the evolution of the species).

Chomsky’s theory is quite plausible: the fact that a child can learn a language easily and naturally within a certain timeframe strongly suggests that our language faculty is genetic. But from the perspective of phylogenesis — the evolutionary process of the species — how should the emergence of language be explained? The existence of languages like Pirahã, which seem to represent an early stage of linguistic evolution, raises valid questions about how much language is a product of social and environmental conditions.

Where Everett falls short is here: language is not merely an invention to meet social needs. Rather, it is the result of a process where biological evolution and social conditions intersect and co-evolve.

From this angle, the Pirahã language is not “primitive” or “deficient” but can be viewed as a living example of the evolutionary history of human language — like a living fossil.

Although Everett and Chomsky seem to be polar opposites, from this new perspective, they share some common ground. By arguing that language was invented by Homo erectus, Everett inadvertently moves closer to Chomsky, who denies that language is simply the result of cultural evolution. After all, the linguistic evolutionary process must be part of the broader evolutionary trajectory that made Homo erectus possible in the first place.

Language is one of the fundamental problems of philosophy — not only in terms of how it originated but also how it carries meaning.

This brings us not only to the origins of language but also to its mental content — its relationship with thought, cognition, and reality. The views of Chomsky and Everett generate entirely different questions and answers about meaning. For instance, if Chomsky’s claim that all languages are grounded in a universal grammar is correct, then meaning, too, must be seen as a universal and innately determined formal structure. But this explanation falls short of addressing why different cultures and communities have different worlds of meaning, because meaning cannot be reduced solely to a biologically determined formal structure.

In this context, I would note the following: Everett says that language is the transmission of information (meaning) through symbols. Chomsky, in contrast, defines language as a mapping from meaning to sound**. Beyond these, however, one could also view language not as a symbolic structure representing meaning but as a structure in which meanings and sounds directly correspond. Such a perspective should again be analyzed in light of the differences between ontogenesis and phylogenesis.

Dr. Azmi Aydın

Yorumlar